Heaven and Hell

Paco Barragán on Dani Marti

CONTEMPORARY October 2006

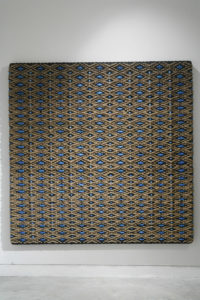

Un fraile y un muchacho (take 1)200×200

Dani Marti is a multi-disciplinary artist who creates powerfully perverse and paradoxical works that delve into topics such as religious dogma, pleasure and pain, innocence, home, and the history of art. Whether realised in painting, sculpture, installation or, most recently, through video, his non-representational portraits are precise, structured, poetic and at times invasive.

To have a better understanding of the driving forces behind Marti’s work it is important to note that this Spanish–Australian artist was born in Barcelona, lived in Australia for 15 years and recently moved to Glasgow. The feeling of not sitting squarely within either culture is central to his art, which reveals how he (re)builds his own identity and how he faces the challenge of fitting into a different culture.

His complex relationship with Catholicism informs his artistic practice in challenging ways, with connotations of mysticism, eroticism and masochism. We should not forget that this pristine sense of guilt goes back as far as the baroque period where the separation between body and mind lead to highly paradoxical artistic representations. The dwarfs, monsters, buffoons, and bearded women that have inhabited Spanish culture from the Golden Age until today – think of Diego Velázquez, Francisco Goya, Luis Buñuel and Pedro Almodóvar – become, in the hands and eyes of Marti, evidence of a forever turbulent and dramatic world vision. This subtle but tense ambivalence, no more than a reflection of Catholicism’s inner contradictions, is thus revealed in his portraits: beautiful mirages, seductive mirrors that give us back an uneasy, even unpleasant, image of ourselves, at the same time providing us with a more tangible interpretation of the world.

Marti’s recent series, ‘The Seven Pleasures of Snow White’, presented last February at the Sherman Galleries in Sydney, consists of immaculate woven patterns of fibres, which nonetheless suggest underlying tensions. Similar to earlier pieces such as Looking for Felix (2000), Linda (2001), Variations in a Serious Black Dress #3 (Alba gently lays down) (2002) and The Last Sins of St. Francis: Scarring the Flesh-Episode 5 (2003–4), these allegorical and apparently minimalist ‘paintings’ are executed in a clean, meticulous and obsessive manner. The baroque fold – in this case hundreds of ropes and cables which fold and unfold endlessly, towards infinity – conforms with horror vacui, every orifice being formally and conceptually filled by the artist; and vanitas, a reminder of the transitory nature of life. The works exemplify a passionate labyrinth where the intricate relationships between the body, eroticism, and power are questioned, reflecting the social, political and philosophical crises of our time.

Thus Marti creates a narrative whose coordinates are revealed by its somewhat Deleuzian titles: A Hundred Lashes, Fascist Desire, White Holes, A Flow of Intensities, A Body Without Organs, Pablo (The Impossible Dream), Throughman (The Yellow Peril) (all 2005) and Un fraile y un muchacho (2006). When we look at these works we experience a certain moral tension caused by its beauty. It is perhaps appropriate to quote here the philosopher Karl Rosenkranz when he states that ‘moral tension is caused by beauty, which camouflages the real and distracts injustice – a beauty that goes beyond good and evil, which expresses the beautiful through the ugly’.

Marti’s recent video works (his first in this medium), deal with the same obsession as the woven pieces: portraiture. While The Stamp Collector (2006) is more abstract and formal work – we hardly see the person, and when we do so it is under the ‘second skin’ of a mask and an rubber suit – The Evils of Forgetfulness (2006) provides us with a greater better sense of the persona, Robert. However, faced with the camera, the character soon slips into a succession of spontaneous performances turning the whole idea of making a portrait into a contradictio in terminis.

For Marti, both weaving and (video) taping represent an act of bondage, a ritual which enables the artist to ‘possess’ the person that is portrayed. Aesthetics, pleasure, fantasy, and security come into play reminding us of Foucault’s ideas about violence as an exercise of power that negatively affects freedom, and through which the dignity of the other is perceived under a new light. It’s a question of faith, of mutual consensus, but also and most importantly about portraiture as an impossible act.

In his work Dani Marti exposes the torture of our spirits, and our desire for emancipation, in a visceral and suffocating way. It is as though the artist wants to remind us that heaven and hell is inside ourselves.

Paco Barragán is an independent curator based in Madrid and the Artistic Director of the Castellón County Council International Painting Prize